Inequality in democracies: interest groups & redistribution

Acemoglu and Robinson have another excellent post at their Why Nations Fail blog. This time the topic is "Democracy vs. inequality".

We are by now more or less aware that income inequality in the US and in most of the rich OECD world is higher today than it was some 30 to 40 years ago. I've discussed the implications behind this increase several times before (see here and here) but the fact remains that inequality is exhibiting a persistent increase, which is robust to both expansionary and contractionary economic times. We might even say that it became a stylized fact of the developed world (amid some worthy exceptions of course). The question on everyone's lips is why would a democracy result in rising inequality?

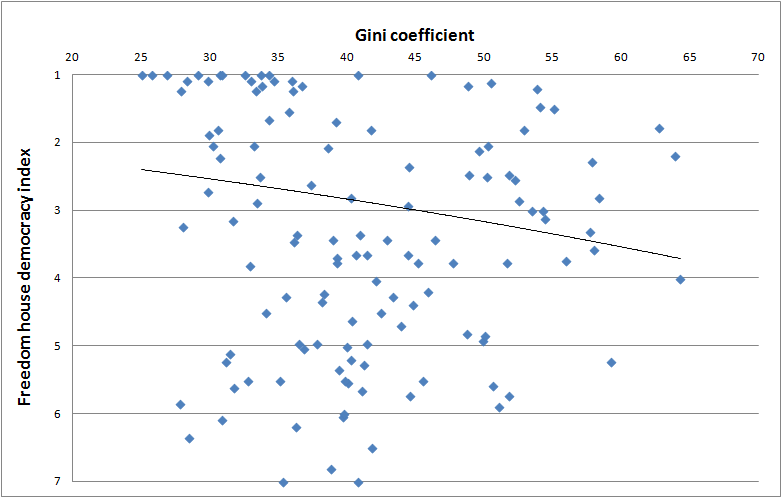

A&R point to one of the seminal papers in political economy, that of Meltzer and Richard (1981), whose theoretical model emphasized that more democracy implies more redistribution and hence lower inequality. The idea is that the median voter is usually to the left of the mean income voter in a typical income distribution curve, which is always slightly tilted to the right (meaning there is more poor people than rich people in a society). The larger the gap between the mean income voter and the median population voter (i.e. the poorer the median voter), more redistribution will be demanded (under the classical Downsian assumptions). Which also implies that more unequal countries should have larger governments. We of course know this is not true, primarily since most unequal societies are NOT democracies, meaning that their ruling elites don't really care of the position of the median voter. But it is true that more democratic societies do on average have lower inequality:

|

| Note: The Freedom house democracy ranking is from 1 (the most democratic) to 7 (the least democratic). Higher Gini implies higher inequality. The graph deploys averages of the democracy index and the Gini in the past 20 years. Source of data: Gini: World Bank. Democracy: Freedom House. |

Note however that this is mere correlation, not even a strong one, and it doesn't tell us a lot on why inequality in the West is still rising.

In their new paper Acemoglu, Robinson, Naidu and Restrepo (2013) discuss several theoretical possibilities of why democracies can fail to reduce inequality. The first is that they get captured by crony elites (something rather common to most newly created democracies, particularly to those of Eastern Europe), who hold de facto power in a society and can thus twist laws in their favorable direction. A newly founded democracy can also result in "inequality-increasing market opportunities ... when it opens up disequalizing opportunities to segments of the population previously excluded from such activities, thus exacerbating inequality among a large part of the population". And finally, democracies can transfer political power to the middle classes instead of the poor, which may not favor redistribution at all.

But none of these factors hold for the US, or any of the rich OECD economies.

Here are the empirical implications of their paper:

- "First ... the long-run effect of democracy is about a 16 percent increase in tax revenues as a fraction of GDP.

- Second, there is a significant impact of democracy on secondary school enrollment and the extent of structural transformation, for example as captured by the nonagricultural share of employment or output.

- Third, and in stark contrast to these results, there is a much more limited effect of democracy on inequality. Democracy just doesn’t seem to affect inequality much. ...

The limited impact of democracy on inequality might be because recent increases in inequality are “market induced” in the sense of being caused by technological change. But equally, this may be because, as in the Director’s Law, the middle classes use democracy to redistribute to themselves. But the Director’s s Law is unlikely to explain the inability of the US political system to confront inequality, since the middle classes have largely been losers in the widening inequality trends. Could it be that US democracy is captured? This seems unlikely when looked at from the viewpoint of our typical models of captured democracies. But perhaps there are other ways of thinking about this problem that might relate the increasingly paralyzing gridlock in US politics to capture-related ideas."

Interest groups

So how come the median voter in the West is still disenfranchised? Shouldn't the persistence and consolidation of a democracy imply a gradual decline of inequality? We can even disregard the fact that this includes most newly created democracies in the 90-ies since the rich OECD countries have had democracy for a long time.

The rapid rise of interest group power can help us provide an answer. As interest groups in democracies get better organised, they become more successful at increasing the size of government but bias that increase towards themselves. This leaves relatively less money for redistribution and programs aimed at the poorer ends of the society, particularly in terms of education and health care. Olson's theory of collective action perfectly explains this phenomenon where small, privileged groups possess enough information, have low enough organization costs, and are far more homogeneous in distributing the potential benefits to successfully solve the public good allocation problem. As the number of interest groups fighting for state redistribution increases, this becomes a wider burden for the society, whose productive resources are being suboptimally allocated. We can call this phenomenon "interest group capture" which unfortunately characterizes more and more democratic societies today (both rich and poor).

Impact of technology

If we can call that the macro reason for rising inequality, then the structural factors such as technology and education, arguably even more important, can be called the micro reasons. It is indicative that the inequality gap started increasing since the 80-ies (as shown by Atkinson, Piketty and Saez, 2011), just around the same time the third industrial revolution started changing the patterns of job market specialization.

As mentioned before, the culprit for higher inequality, in my opinion, can be found in the interaction of several factors. Rapid technological progress in the past 30 years resulted in a typical creative destruction process where new jobs and careers made certain types of old jobs obsolete (automated work). Some of these obsolete jobs were outsourced to Asia (even though one phenomenon followed the other, this doesn't imply a direct link of causality; one has to test this hypothesis to see if it holds). In addition, a lot of low-skilled labour entered the market (mostly via higher immigration) who failed to adapt to the changes and were left stranded either at lower paid jobs or became long-term unemployed. Poor education played an important role as well, while stagnating wages in the "dying" sectors only widened the gap. On the other hand, the innovative part of the equation was working quite well taking advantage of the new technological wave, thus further raising the income of the top 10% (hence the great disparity between college and non-college degree workers). It's not hard to imagine how these two pulling forces (one downwards, one upwards) managed to widen the US inequality gap.

However none of these issues affected the real US problem: stagnating social mobility. The underlying causes behind this structural phenomenon can indeed be blamed on interest group capture of democracies. The solution to this problem is thus, primarily political.

this is one of your best posts so far! in my opinion.

ReplyDeleteLinking interest group capture to inequality is a very unique approach to thinking about this, I would say, widely misinterpreted issue

thanks!

DeleteI agree it is widely misinterpreted, which is why I rather put an emphasis on social mobility which is a far bigger problem in the US and beyond right now