"Yes, Economics is a science, but many economists are not scientists!"

This title is actually taken from Paul Krugman. For once I agree with him.

Chetty draws an interesting parallel with medicine:

A social science

The problem with quacks

Krugman's blog came as a response to a great text by this year's John Bates Clark medal recipient Raj Chetty from Harvard. Chetty wrote a column for the New York Times this weekend where he defended the field of economics on the basis of its scientific rigor. His text came as a reaction to many non-economists questioning the recent Nobel prize being awarded to two opposing theorists explaining the same phenomenon (Fama and Shiller), but also (I believe) to a series of texts about economics and philosophy started in the NYT back in August, initiated by two philosophers Alex Rosenberg and Tyler Curtain writing a text called "What is Economics Good For?". Their main resentment towards economics is the imprecision in its predictive abilities. Or in other words, economics, with all its new modern analytical tools, not only couldn't predict the crisis, but is also failing to solve it. This caused a series of immediate reactions from many notable names including Krugman, Vernon Smith, Eric Maskin, and a number of others that carried on the debate. The debate actually never stopped since the origination of the financial crisis, when many wondered why economists couldn't have predicted neither the severity nor the length of the crisis. Its ambivalence over what the actual causes were, and consequentially what the best solutions could be are only causing further discomfort to the field.

But luckily, many of those who did step in and defend the field handed in some pretty persuasive arguments. Maskin made a good point in saying that prediction isn't everything, comparing economic predictions to those of seismology or meteorology, where neither of the two can be a 100% accurate in predicting when an earthquake is going to occur or whether or not we're in for a sunny day or a rainy day. Economics is more about explanation. Just like any social science, it will never make perfect predictions, but it will provide us with a detailed understanding of many phenomena. How does this differ from every other science? Can medicine be absolutely sure in the effectiveness of one treatment method over another? No. At least not with a 100% certainty. But no one ever questions the scientific methods behind medicine. And rightfully so.

"It is true that the answers to many “big picture” macroeconomic questions — like the causes of recessions or the determinants of growth — remain elusive. But in this respect, the challenges faced by economists are no different from those encountered in medicine and public health. Health researchers have worked for more than a century to understand the “big picture” questions of how diet and lifestyle affect health and aging, yet they still do not have a full scientific understanding of these connections. Some studies tell us to consume more coffee, wine and chocolate; others recommend the opposite. But few people would argue that medicine should not be approached as a science or that doctors should not make decisions based on the best available evidence."

The proper usage of models

Economic models used for making predictions also raise many eyebrows from the regular folks. But economic models are just that - models. An approximation or better yet, a simplification of reality, not meant to be perfectly applicable, since all aspects of a complex environment cannot be included in a model (they are determined exogenously, i.e. outside the model - a crisis is a good example of such an unanticipated, exogenous shock).

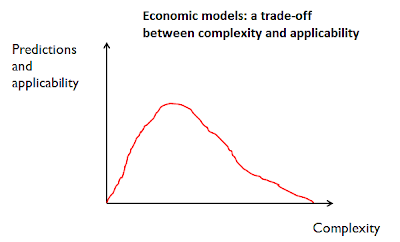

Models operate under a delicate trade-off between complexity and applicability. If you make them too complex by trying to include too much stuff in there (culture, socio-economic preferences, informal institutions, etc.), you end up getting very little predictability. If on the other hand you make them too simple, you again get low applicability. The key is to reach some satisfactory level of complexity so that you can maximize the predictability and applicability of a model (almost like a Laffer curve). But in neither scenario does it imply a perfect mechanism for making predictions. Their purpose is to design a hypothesis which needs to be tested empirically and/or defended theoretically - so in both cases it requires a scientific method to support it.

A social science

Empirical methods in economics are not as robust as those done in say, physics. Take this example; before being sure that the researchers at CERN have actually discovered the Higgs boson, they wanted to be sure up to a 6 sigma standard deviation, i.e. at a margin of error of 0.0001%, while for economists, anything between a 1% to 5% margin is good enough (this is the so called statistical significance used in econometrics). So even though economics is less precise, this has a lot to do with the fact that economic social experiments are much harder to do in the real world. As Chetty says, one cannot perpetuate financial crises over and over just to learn how to solve them. Unlike natural sciences, here we're actually messing with peoples' lives. But one can actually do economic policy related experiments thereby testing the efficiency of a certain policy, as Chetty notices. All one needs to do is make an experiment with one treatment group and one control group in order to examine the effects of a particular policy on the treatment group, and how their behaviour or actions differ from those of the control group. This is how we capture the causal effect (the average treatment effect on the treated).

Apart from policy experiments, one can also use economics to establish monetary or fiscal policy rules, like the Taylor rule (which was abandoned in the pre-crisis decade, mostly because of a need to respond to the 2001 IT bubble when the Fed created scope for the housing bubble). Or in fiscal policy one can test and establish things like the limited budget deficit - to curb the politicians' incentives to misappropriate budgets. One can also establish debt ceilings to control public debt...oh wait, that one doesn't work that well actually, does it?

Economics is too closely interlinked with politics, so demanding answers only from economics without thinking of the political implications is a faulty approach. For example, many economically sound ideas on which >90% of economists agree upon - like free trade, immigration, the efficiency of subsidies, a number of empirically proven models and theoretical concepts (stylized facts ranging from public choice theory and institutional economics, to basic micro and macro models), or the basic price mechanism and the simple dynamics behind the laws of supply and demand - will never be implemented by politicians who care only of satisfying and protecting partial interests in order to remain in power. So when you think about the soundness of a certain fiscal policy, tax rate, or budget spending, have in mind that behind that decision, it's not an economist, but a politician.

Detaching science from policy

Many critics of economics as a science are persistently confusing economics and economic policy. The field of economics does contain scientific method, but economic policy is mostly craft. And in order to "sell" an economic policy to the public, one needs to have good "sales skills". This is where politicians step in. But how often do you see politicians actually calling upon relevant economic research? Only when it supports their ideological viewpoint.

Which brings us down to Krugman's argument. His reaction on Chetty's text was spot on. He agrees that economics is indeed characterized by scientific method, however he also emphasizes that many economists don't do much science at all:

"The point is that while Chetty is right that economics can be and sometimes is a scientific field in the sense that theories are testable and there are researchers doing the testing, all too many economists treat their field as a form of theology instead."

He cites Chetty's examples of empirical research being done on the health insurance policy in Oregon, where a genuine randomized experiment was conducted with a well defined treatment and control group. Krugman is outraged that many conservative economists don't like to take this evidence supporting Obamacare for a fact. And he has every right to be outraged. But what about other empirical facts that many liberal economists tend to disregard? Such as the inefficiency of state stimulus programs, or the fact that the deficit and debt busts were caused by bailouts not the crisis - something Krugman is actually holding a pretty tautological view of?

This is a good example of conflicting opinions among economists, where the issue at hand is either highly controversial or on which economists are still unsure about. But with upcoming decades of vigorous research, relevant policy solutions to these issues will surely be given. The question is how likely are they to be implemented by those in power?

The problem with quacks

Conflicting theories in science will always exist, and are in fact welcomed as out of opposing views usually arise the best ideas (avoiding the confirmation bias). But economics tends to be attacked more than any other science on the soundness of one approach over another. The reason is simple: during bad economic times (as we have now) many forgotten fallacies of the past suddenly get rediscovered. Why is this? A partial culprit is believe it or not - the media. In search of explaining a certain phenomenon the press likes to match opposing economic ideas; one being the so-called "mainstream", and the other "the alternative". Even though sometimes the alternative proposals can indeed be quite sound (it all depends on how we define mainstream), in most cases they are not. Too often a lot of space is given to obscure economists (quacks) offering their own quick fixes without any scientific method whatsoever standing to confirm their findings, and without ever considering even the basic effect their misplaced ideas might cause on systemic stability. But since debates on economic topics are much more popular and widespread than debates on topics in physics or chemistry, these quacks tend to get a lot of media space to push forward their ridiculous and washed up ideas.

You can surely find the same thing in every science (how many times have you seen people claiming to be scientists talking mostly nonsense? And it wasn't because they weren't "mainstream", it's just that their conclusions are often completely senseless). However, in economics these quacks tend to be much more widespread, particularly when non-economists start thinking they have a magic idea of how to fix the system. Most of these people are luckily never taken seriously, but some tend to attract quite large crowds of followers. It is because of this that a lot of people seem to think economics is mostly hokum, and it is precisely because of this why economists must react and explain to the public the crucial difference between economic policymaking and economic science. Economic science must always stand to support economic policymaking. When it doesn't, markets start to crash.

You can surely find the same thing in every science (how many times have you seen people claiming to be scientists talking mostly nonsense? And it wasn't because they weren't "mainstream", it's just that their conclusions are often completely senseless). However, in economics these quacks tend to be much more widespread, particularly when non-economists start thinking they have a magic idea of how to fix the system. Most of these people are luckily never taken seriously, but some tend to attract quite large crowds of followers. It is because of this that a lot of people seem to think economics is mostly hokum, and it is precisely because of this why economists must react and explain to the public the crucial difference between economic policymaking and economic science. Economic science must always stand to support economic policymaking. When it doesn't, markets start to crash.

The biggest problem for Economics is that which afflicts the other social sciences, and that is the twisting or bastardization of the science to bring about certain political outcomes. (I am thinking of the Neo-Keynesians here mostly)

ReplyDeleteI would rephrase the title in that economics isn't a science, but some economists are scientists...if that makes any sense

ReplyDeletePrediction isn't everything, but if a large part of the discipline is making predictions and most of those predictions are systematically, repeatedly found to be incorrect subsequently, then that brings into question any claim of the fields claim to be well developed science.

ReplyDeleteThe post slides all over the place with its conception of science - one minute the inconclusive nature of economics is explained with a disclaimer that the faults are merely a natural attribute of a 'social science' but then elsewhere in the post it is implied that economics is a science like seismology or meteorology which are not under the category of social science.

Non-economists may give a valid critique of mainstream economics just as a non-theologian scientist can give a valid dismissal of theology on scientific grounds.

The problem with the models of conventional economics is that they often rely on a premise that is so absurd that they fatally undermine the credibility of the model as anything other than a contrived intellectual exercise.

If the predictability and applicability of the economic model is one instance in a thousand you could still argue that you had maximised the predictability and applicability of the economic model. But this wouldn't mean the model would be very effective to use in policy making.

The appeal to the majority that you make, (90% of economists believe X...) along with the appeal to authority, suggests you are rather over reliant on logical fallacies to shore up your argument. However Im not saying everything youve said is wrong as you are probably right in accepting the traditional economics view of the price mechanism, and correct in pointing out that power corrupts.

There has been no scientific testing of the hypotheses that state bailouts cause deficits, because no state bailout was done within the framework of a scientific test. Your implication that this happened is entirely spurious.

The scientific method cannot be used in demonstrating the truth or falsehood of stock economic ideas, or the suitability of the ideas of economic theory for systemic stability or otherwise. Your idea that the economists are those whose ideas are backed up by the process of science and verified by the scientific method is utterly false. You cannot test with an experiment your hypothesis that free trade is the best, because free trade is not possible at present or in the next few years, thus no experiment can be done relating to free trade in the economy. Thus the scientific method has not, and will not be used to demonstrate the validity of the thing that economists insist upon ('free trade being the best form of trade'). Therefore your claim to have established by the scientific method that free trade is the best type of trade, is unscientific quackery because you cannot carry out a process using the scientific method to determine the veracity or otherwise of your idea about free trade, it is just an ideological belief. So your claim that the economists are scientific while the non-economists are quacks on these matters, is entirely wrong.

You cannot analyse the data from your experiment on the effects of free trade in an economy with a control of protectionist trade, because no such experiment has taken place or could take placde, therefore it is the tradional economics free trade position which is quack ie unscientific.

Thanks for the detailed comment, but in most parts you've missed the point of the text. I accept that this is partially my fault for not being clear enough (although you can only fit so many words in an article).

DeleteAnyway, the claim against quacks is mostly aimed at those within the economic profession. Those outside of it simply notice a lack of coherent ideas within the field and aim to supply their own, but they often make simplification errors when doing so. However, this is a debate in its own, far too complex for the comment section of a blog.

Regarding the free trade idea, I never mentioned its scientific falsifiability, only the fact that over 90% of economists agree upon it. You're right, it hasn't been scientifically proven or disproven. It fails the Popperian test.

The point here was to detach economics (as a science) from economic policy. This is the first step towards vindicating economic research and making it somewhat applicable (particularly in fiscal and monetary policy). By doing so one effectively gets rid of quacks from within the profession (the snake oil sellers, many of which featured prominently in the media).

The next step is then to apply the Popperian scientific method and reach a consensus over which policies are effective, which aren't, and to which we're simply completely blind to.

Finally, bailouts and debts. During the crisis, countries paid billions and trillions to bail out their banks. The way to pay for the bank bailouts was to take on more debt (they didn't finance the bailouts from increasing taxes nor by printing money - at least not all of them). Therefore more public debt is a direct consequence of bailouts. There is no ambiguity in this question. As for the deficits, in many countries higher levels of debt increased borrowing costs which worsened the domestic public finances. How? By increasing interest payments which increased the spending category in the budgets. Therefore, the deficits widened. Again, no ambiguity here. (perhaps you also take into account other factors that increased the deficits - there's no doubt about it, higher unemployment played a role, as did firm bankruptcies, but over-excessive debt accumulation used to finance the bailouts was the main source).

Wow! The personal statement economics is too closely interlinked with politics, so demanding answers only from economics without thinking of the political implications is a faulty approach.

ReplyDelete