Understanding the "growth problem"

Buttonwood, a columnist in the Economist, had a recent column on the "Growth problem" in the West. He seems to hold strongly to the austerity vs. growth paradigm and claims that the issue of declining economic growth has been a problem in the West for quite some time:

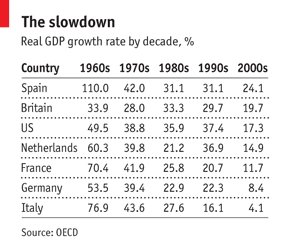

Source: Buttonwood, The Economist "But it is worth remembering that Europe's growth problems did not start in 2010. As the table shows, real growth rate in the six European countries featured above has been slower in each successive decade (on average); the drop between the 1960s and the noughties was a staggering 54 percentage points. The US, which is shown for contrast, saw fairly steady growth from the 1970s to the 1990s before dropping off this century.

...It may well be that European economies would perform better collectively if austerity programmes were relaxed. But it is a stretch to believe that Europe can return to the growth rates seen in the 1960s or even the 1970s. And those rates might be needed to make the debt problem go painlessly away."

Yes, it is a "stretch" to believe that Europe can return to the 60s and 70s growth rates, but there is a good reason why this is the case - convergence theory! Moving to a higher, more technologically advanced level of development, as these countries have done relentlessly in the past half a century, implies a slowdown in economic growth. One cannot repeat post-WWII growth rates for 50 years. They only last for a decade or so, while the subsequent path of nations is to converge to an upper steady-state level of wealth. This was the case in Europe, and the obvious consequence was a significant increase of living standards and personal incomes. Convergence theory can teach us one thing: that if you have lower GDP p/c you're much more likely to grow faster.

Economic growth by itself isn't the goal. The goal is to use rapid economic growth to reach a sustainable level of development, as the aforementioned countries did. Rapidly growing BRIC nations should take note here and use the accumulated economic wealth to increase the living standard of their populations and achieve a higher level of development. As the WEF's Global Competitiveness Index explains, this means moving from a factor-driven or an efficient-driven economy to an innovation-driven economy. The danger is to get stuck in a transitional period (between an efficient-driven and an innovation-driven type of development), as this implies that something was wrong with the growth model applied in the economy.

He's right about one thing though:

"A company can borrow to invest and a society can too. But there is not much evidence that the debt has been used to finance productive investment; it seems to have gone on speculation and consumption. We have "borrowed from the future" and are suffering accordingly."

This was an unfortunate case in some of Europe's countries, but not for the whole group. The different growth models applied in pre-crisis times are creating a new divergence in Europe - on one side those who borrowed to finance productive investments ("the core" - even though this is arbitrarily defined), and those who borrowed to finance private and public consumption ("the periphery"). If you can expect any higher growth in the future it's most likely to come from the "periphery" and their catching up with the "core". However, don't expect to see 50% across decade growth rates in Europe in any country, not because their growth model is wrong, but because their development level is high.

great text! the long-run decline of growth to say 2-3% on average for developed economies is a normal occurrence. It's ridiculous to expect CHinese-style growth in Europe anymore (at least in the developed Europe).

ReplyDeleteBut it's also important to at least reach back the 2-3% growth that we should have.

No doubt, restoring the pre-crisis growth trend is achievable, and we can even say that some stronger growth is expected as the labour force bounces back into employment, but it will never again pass double digits. And there is a good reason why this is so..

DeleteI have to say I am not a big believer in convergence theory. The slowdown we saw in growth coincided pretty well with the growth of a huge bureaucratic and welfare leviathan in all of those nations. I do not think the slowdown in growth was inevitable.

ReplyDeleteIf there is any inevitability it stems from the following dynamic:

Nations which are capital intensive create large production costs (especially on labor) and must maintain high productivity in order to grow. Eventually the capital begins to flow to nations with low wage costs. Thus the bulk of the low end products (textiles and cheap consumer goods) are produced in less capital intensive nations, as is now the case with India, China, and Indonesia leading the way.

Very good explanation Kyle! But this can as well be attributed to a restructuring of industries and jobs in the West. We can easily say that technology is playing a very important role here as well (see here or here).

DeleteAs for the slowdown due to an expanding welfare state, yes it can explain some deviation from high growth rates, but it cannot be the only explanation of why the West isn't growing at 50% per decade. We can call it diminishing returns from the existing combination of factors of production. And again technological improvements ensure that these diminishing returns never turn negative but always keep growth rates positive. Every once in a while there's a tech shock which creates a new combination of factors and it's up to the market participants to adjust to it. It's important here not to prevent this too long (as governments often do).