EU elections comment: Marginal parties do well in marginal elections

The success of extremist parties in the latest vote for the EU Parliament shouldn’t come as a surprise, even though it is a slight reason for concern. The agendas and activities of some of these parties such as the French National Front, the Greek Golden Dawn, or the Hungarian Jobbik are just too gruesome to comment. Far from their anti-immigration agendas and their protectionist economic approach, they are examples of the exact sort of thing the foundation of the EU was supposed to avoid – the rise of Nazism.

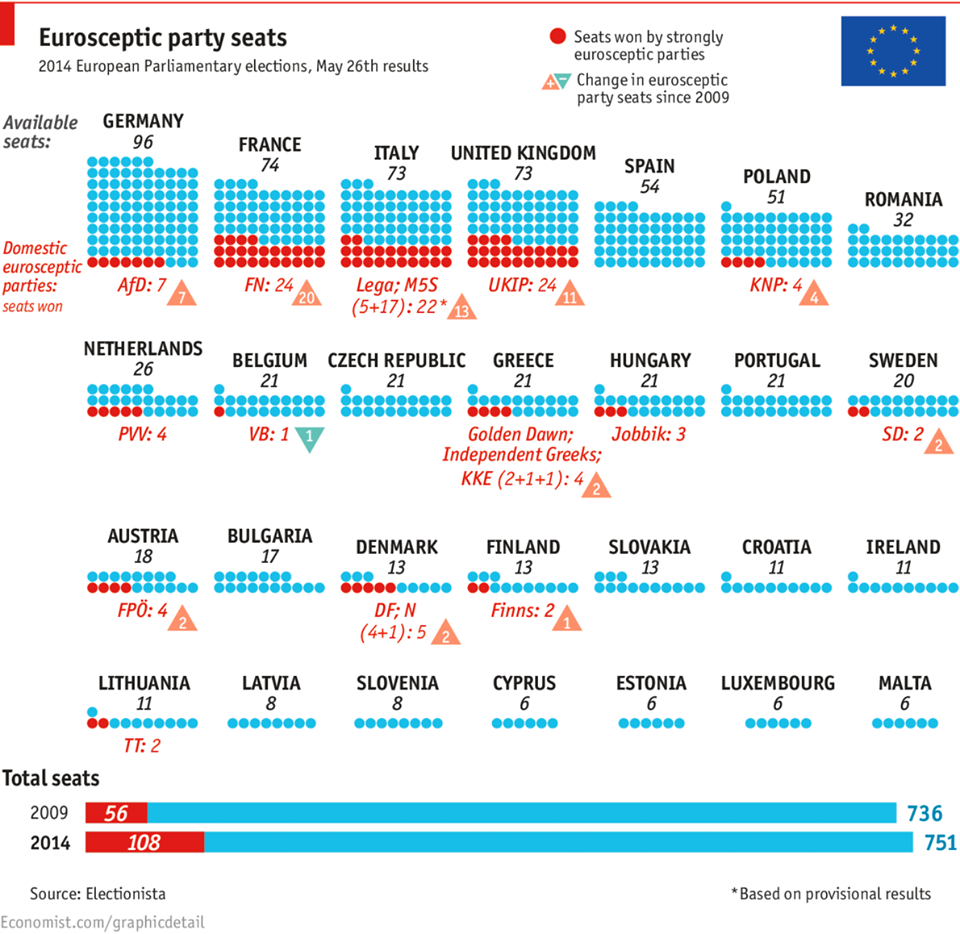

In addition to their almost identical national-socialist pleas, one thing all of the marginal right-wingers have in common is a Eurosceptic agenda, which in most cases calls for the abolition of the EU itself. To stress the absurdity of the situation, imagine that one fifth of the national parliament of a country consists of people who despise the country itself and seek to destabilize it. Their Euroscepticism is the glue holding their interests together and by using it they’ve managed to build a big enough support group of disillusioned citizens tired of Europe’s bureaucracy and the perception of political dysfunctionality in times of crisis.

|

| Source: The Economist |

The reason for their success is primarily low turnout. European Parliament elections are a second order election. They are insignificant in their importance, in their scope, and in their effects. They represent a perfect platform for marginalized political parties to grab some attention as it is in such elections where their supporters tend to turn out in large numbers, while the majority of other voters rather stay home (on average across the member states). It would have been even worse had turnout been lower, since these elections for the first time ever averted a declining trend, with total turnout being a still low 43.1%.

The second reason for success is their perception as an anti-establishment movement. In times when most European countries are suffering from an ill-advised austerity approach where everything but credible institutional reforms has been tried, the electorate has gotten fed up with the dominant establishment centre-left and centre-right parties. Their response isn’t to vote against them as they have no one good enough to turn to, their response is simply to stay home and avoid participation, thus non-intentionally leaving more room for extremists to be heard.

The voters realize that in terms of economic recovery one should look far beyond the scope of the EU Parliament and the EU Commission. The role of the Parliament and the Commission are developmental and redistributive, not reactionary; the EU budget is focused on agricultural subsidies, structural funds and investment into education, which are all noteworthy goals, but neither can help Europe achieve a robust recovery. The Commission simply doesn’t hold any mechanisms to resolve structural problems of member states. They can propose regulatory solutions that may prevent future shocks (such as the banking union idea), and can facilitate free trade and movement of labour and capital, but they cannot solve member states’ structural problems in lieu of their governments. One cannot expect things such as the Single Supervision Mechanism or the euro-wide Deposit Guarantee Scheme to be the key for kick-starting economic growth. They are a good response to the problems of a currency union, which should have been addressed earlier, but they aren’t policy measures that can help solve crises. For economic recovery national elections are still much more important than EU elections.

In that perspective one cannot really expect much from any of the Parliament members, or the so-called euro government, but precautions still lie ahead in terms of domestic politics.

It seems that the long-lasting consequences of a deep economic crisis have finally resulted in their most dangerous consequence – a rise in popularity of previously marginalized extremist political parties across Europe. Even though they’re still not strong enough to influence national policies, Europe should take caution as this is exactly how the Nazis in Germany started in the 1920s. After a decade of political marginalization and ridicule from the mainstream media, the German hyperinflation had finally made the electorate cave in and gave them power. This may seem as a distant scenario in terms of domestic national elections today, but it is precisely the European Parliament where the extremists are given a chance to stand in the limelight and advocate their economically backward and failed ideas (nationalization, protectionism of domestic industries, modern mercantilism etc.) which tend to attract a surprisingly large amount of people in times of economic hardship. The extremists won’t dissolve the EU, nor will the EU Parliament be the place where one might expect an origination of economic recovery, but the economic reforms in member states should start quickly before it is too late and Europe once again loses hope and descends into nationalism.

Comments

Post a Comment