Graph(s) of the week: Budget numbers

Still on the UK 2012 Budget. From the Budget 'Red book' and the OBR report, I have found a few interesting graphs.

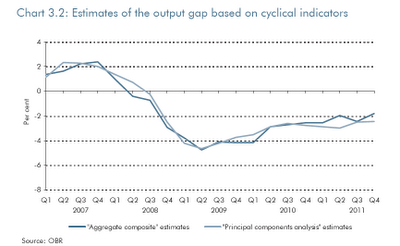

First one is from the OBR, showing the UK output gap:

|

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility: Economic and Fiscal Outlook, pp. 39 |

Is the shock that hit the UK economy in the crisis permanent or temporary? In other words, is the GDP trend line for the UK going to readjust to a lower steady state level, or is the GDP growth expected to bounce back shortly? Perhaps according to this the UK GDP is likely to return to its pre-crisis trend line, however in a much longer time span than anticipated. This only shows the size and effects of the distortion created during the crisis and the fiscal shocks (internal and external) that hit the country and reduced its productive economic capacity. Looking in the long run, any shock is temporary, even though a longer recovery will shift the medium term trend line a bit downwards. A completely different question is whose fault is it that the recovery is so long or whose fault is it that the output gap is still negative, around minus 2%.

The second graph is from the Budget 'Red book', and is showing a forecast of the government's commitment to reduce the budget deficit by 2016/17 (the actual balance is not shown):

|

| Source: HM Treasury, 2012 Budget, pp. 18 |

Observe the huge gap as the Brown government decided to bail out the British banks. The result was a completely unsustainable fiscal position that had to be punished on the elections in 2010. The current government is sticking to its commitment to cut spending, which the numbers clearly show and which is the primary source of attacks against British austerity from many of its critics. But even though public sector cuts are obvious and welcomed, other areas of private sector intervention are not. For the British austerity case, I refer the reader to a former post.

Finally, here is a short cost-benefit table of the budget, from the Economist:

|

| Source: The Economist, "A big splash with little cash", 24th March |

As it can bee seen, the announced policies are likely to produce a net benefit by the end of this year, while resulting in a net cost in the following year (which is still only around 0.1% of the GDP). By far the largest loss of revenues is to come from the increased personal allowance. This will be partially offset by a series of small measures such as the 'granny tax', the increased bank levy or the reduced special spending reserves. The stamp duty on expensive homes (the mansion tax) will bring in a total of only 400m, which makes it hard to justify from any other perspective besides a political one.

I was asked the other day whether I think the Budget was still a Keynesist policy response, a supply side reform (because of decreasing tax rates, reducing red tape in planning, and even announced road privatization), or something in between. My answer was yes, Osborne is still a Keynesian, as he still tends to believe that the government can pick winners (gaming), still wants the government to drive the infrastructural growth and still wants to stimulate the businesses to grow, by trying to influence the prices of credit. Even though corporate and personal income taxes did fall, and the personal allowance was raised so that more people are taken out of taxation, some elementary mistakes of guiding private sector hiring (youth contract) and investments still exist. This budget was, as I said, an improvement, but not the complete policy for growth.

UK can expect only the slowest and weakest of recoveries as long as the Keynesian model is followed.

ReplyDeleteNever before have people clung so tenaciously to such a discredited idea.

oh I believe the society can get pretty hung up on discredited ideas..this is not the first case nor will it be the last one.

DeletePerhaps you meant in the field of economics - that might be the case, yes.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI think you made a mistake there: "Even though corporate and personal income taxes did rise" - I assume you meant fall.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I agree, the Budget is still Keynesian and I was mostly disappointed by it. There is too much politics in the whole thing, and this is the biggest reason behind a sluggish recovery. No one has the guts to pull off coherent and hard measures to pull us out.

As long as this is the case, the output gap will continue to be negative and the trend will eventually adjust downwards...

Corrected, thanks!

DeleteDoes the output gap mean that the trend-line for the UK be lower from now on? Does this mean that the UK is likely to expect lower long term growth in the future (e.g. 2% instead of an average 3%)?

ReplyDeleteNot necessarily, even though such a scenario isn't excluded.

DeleteIf you'd look at the US trend line after the Great Depression (see first graph here) the average pre-Depression trend line was overshoot during WWII. In the same link you can observe other countries and their shocks of which some were temporary (Sweden, Argentina, Columbia, Philipines) while others were permanent (Spain, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia). In that post Mark Thoma makes a good comparison of the 90s crises in Sweden and Korea where it seemed that both are on for a permanent shock and a lower long run trend line (see here), but eventually Sweden experienced a bounce back while Korea is still in on a decreasing trend.

That's why it's hard to tell from today's perspective what is more likely to happen for the UK. Even after two years, if this continues it will still be uncertain which of the two scenarios will be applicable. Shocks in economics are always unpredictable, that's why forecasters and empiricists hate them.