Five years after the crisis: the consequences

Having portrayed some of the causes and implications of the financial crisis in my previous blog post, in this one I will focus on the consequences and how the countries struck by the crisis are doing today.

First off, what has really changed since five years ago?

|

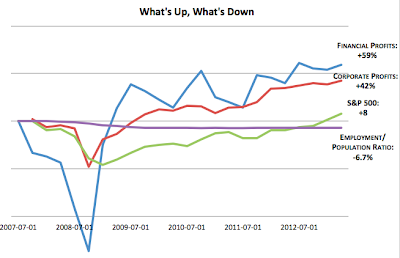

| Comparison of US financial and corporate profits, S&P 500 performance and the employment-population ratio. Source: The Atlantic |

The quick answer is not much. But the devil is in details. The graph above clearly states that corporate and financial profits have recovered quite significantly, while the E-P ratio remains to be dreadful. An obvious conclusion emerges. The real sector of the economy is entering a new equilibrium and the labour market is yet to adjust. The structural shock has altered the patterns of production and labour market specialization, and it's going to take time for the demand for skills to adjust. The IT shock and the outsourcing trend were among the strongest disruptions on the labour market, whose shocks weren't really being felt until the crisis had started. As I've pointed out so many times before, the crisis was the trigger mechanism for the beginning of the restructuring in the labour market, the forces of which were initiated many years before the actual start, but to which many market actors didn't react on time. Add to this various technological improvements like fracking and it's obvious that the pace of technological progress is still not slowing down. As a consequences new markets will emerge, new companies will rise, new occupations will be created, and a new skill-set will be required. This is likely to last for quite some time, even more so as certain government protection activities undermine a quicker restructuring.

When asking the people, they confirm the initial feeling that not much has improved during the recovery, and furthermore that the US financial system isn't as secure as it was before (or at least how it was being perceived before). According to the survey from Pew, a majority of the population still believes that household incomes and the situation on the jobs market haven't changed at all. The majority also believes that real estate values have somewhat improved, while the stock market has significantly improved. Comparing this to the graph above, it seems that the people have an accurate perception of the economy.

When asking the people, they confirm the initial feeling that not much has improved during the recovery, and furthermore that the US financial system isn't as secure as it was before (or at least how it was being perceived before). According to the survey from Pew, a majority of the population still believes that household incomes and the situation on the jobs market haven't changed at all. The majority also believes that real estate values have somewhat improved, while the stock market has significantly improved. Comparing this to the graph above, it seems that the people have an accurate perception of the economy.

However this is an expected reaction to the aforementioned forces operating on the labour market. And since they're likely to continue for quite some time, the short-term implications are looking to stay gloomy in the years to come.

Cross-country effects

But even with the troublesome state of recovery and with many open questions on financial system safety in the US, at the moment the country doesn't look like a place ready to burst again. We'll have to wait for another boom to bring the new instabilities back onto the surface.

The same cannot be said of the Eurozone. Even though things aren't nearly as unstable as they were back in 2011, the structural issues of many peripheral countries still persist, unemployment is running high, growth is anemic and not much is being done in terms of reforms. Europe's debt problems are still increasing despite the austerity pain inferred upon its people. European banks were more infested with bad assets than their american counterparts, however they have written off less debt and are still not out of the gutter. The way European policymakers have decided to handle their austerity policies (tax hikes without real spending cuts - the worst combination for growth) proved to be a terrible solution as they haven't worked in cutting down debt, the deficits are still high, while growth is nowhere in sight. So far Draghi's promise of doing whatever it takes to save the euro is the only thing holding it together.

Britain is in a similar position where weak private sector investments haven't really helped the country bear the pain of deep budget cuts, while the shy recovery is being driven mainly by a recovery on the housing market, similarly to the US. Britain's main concern is its declining productivity, which is a good explanation of why even though the job market is improving, GDP is still stagnating. In addition, on the business investment market, supply is weak as SME funding is still 20% down since 2008, while on the demand side business owners are still reluctant to take on new risks.

Japan is still over its head in debt, with Abenomics not looking likely to fix this anytime soon. But Japan is specific due to its lost decades and the responses to the 1990 bubble burst. It's not a typical model of anything so one needs to be careful in evaluating the short-term effect of its standard economic policies.

By now, we can say the crisis has switched to the emerging markets which are not only worried about their growth slowdown, but also on the next possible Lehman-type catastrophe awaiting to happen in China. Unlike China, the rest of the emerging world is much more vulnerable to global financial flows. The lack of capital investments is driving down currencies and making it hard to finance current account deficits. When the Chinese bubble blows, it's going to be tough times for its main trading partners in the "third world".

Despite no new financial crisis being on the horizon any time soon in the West, global finance is still a long way from being safe. Or at least it's a long way from the perception of being safe as it was before.

Comments

Post a Comment