What’s behind Iceland’s rapid recovery?

|

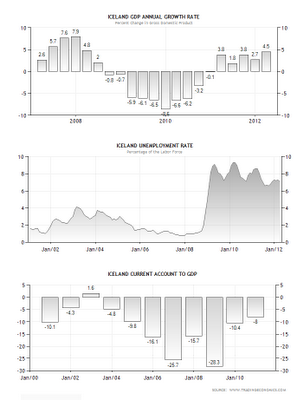

| Source: Trading Economics |

Iceland’s crisis and recession went down much harder than in most European countries (well, except Greece). Cheep credit and (unobserved) accumulation of systemic risk in the early 2000s led to a substantial distortion of signals sent to the real economy. They had a huge exposure to the US financial system with assets tied to many US subprime mortgage-based securities. The post-Lehman collapse followed by the subsequent bankruptcy of Iceland’s overleveraged banks was hardly a surprise. The state interfered by protecting domestic depositors, not allowing the taxpayers to take the burden of a bailout. But this didn't stop Iceland from leading a first case of a trial against a PM for mishandling of the crisis (accused for "negligence"). Mr Haarde was later found innocent by the countries’ courts, but it was nonetheless a strong message sent from Iceland on the seriousness of what happened back in those years. The GDP fell during his prime-ministership for 10% in 2009 with a sevenfold increase in unemployment (see figure). Three biggest banks declared default on more than $85bn of debt which led to a decline of the currency and the economy.

He’s not the only one on trial though – the trial on bankers seems much more important to the nation. This is perceived to be the quickest way for the people to forget all the misery that happened back then. And as long as there is someone to blame, the voters will always be satisfied. In fact, there are even claims that the trials and the determination of the new government to criminally prosecute all those deemed “responsible” for the crisis could have contributed to the rise in consumer confidence across the country.

What happened?

The banks were expanding their asset size built on huge leverage. They were borrowing from foreign lenders and used this money to finance their asset purchases (mostly US MBSs). The increase of prices in the property market (another bubble very similar to Ireland or Spain) induced households to borrow even more. Bank debt and household debt plummeted, reaching levels of up to 6 times of Iceland’s GDP. Households acquired debts of more than 200% of their disposable income. Iceland therefore wasn't a story of a government running high debts and being fiscally irresponsible, but of the private sector running high debts and banks getting over-leveraged and overexposed to risk (again, similar to Spain or Ireland). The problem with the government was corruption and aligning of the in-office party with the banks that eventually went under (that's why the trials were necessary - see more here).

Even when the interest rates started rising, the growing bubble couldn’t be sustained as foreign investors seized the opportunity of an attractive investment in Iceland’s government bonds, supported by a strong currency (which had to be sustained since the domestic households were borrowing in foreign denominated currencies with low initial interest rates – a strong krona ensured that these loan repayments stayed cheep).

As a consequence Iceland experienced high current account deficits throughout the decade (see figure above). This implied, just as in the peripheral eurozone scenario, that a lot of foreign capital was entering the country. When assessing the CA sustainability, it is important to see where the inflows ended up. In the Icelandic case, as shown above, it mainly fueled the property and asset bubbles.

Once outside contagion took place (Lehman bankruptcy), it resulted in a rapid decrease of asset prices meaning that both banks and households found themselves on the brink of bankruptcy. So essentially, it was the same story as with peripheral eurozone.

Recovery and deleveraging

No, it still isn't applicable to Greece

But Iceland reacted differently. Instead of bank bailouts (like in the US, UK, Ireland, etc.), it opted for defaults of the banks. It only protected the domestic bank account holders. This enraged all foreign depositors (particularly the British) even though the new government pledged to return its debts gradually.

The next two steps Iceland undertook is the focus of many in the economic profession as the reason of why Iceland succeeded - currency devaluation and capital controls. The krona devalued 50% against the dollar making Iceland's exports (fish) and tourism cheaper and more attractive. It was these two industries that flourished and mostly helped form the increasing growth Iceland is experiencing for 6 quarters now.

Ever since the crash Iceland has worked hard in restoring macroeconomic stability and rebuilding its financial sector. They received help from the IMF ($10bn) and have pledged to a 3-year restructuring programme. After three years we can surly say that the programme was a success leading to a 2.5% GDP growth following last years’ 2.5% growth. The NGDP is still below its trend line, but it is on a good path to recovering.

However, the most important thing proved out to be that Iceland allowed its banking sector to collapse, not socializing its losses. The government did protect the domestic assets, but foreign creditors were the ones who took the majority of the loss. The government is now looking to pay them back, but at a slow pace. The UK and the Netherlands were most struck by this decision, since these governments stepped in to repay the losses to their own people who lost out in Icelandic bank accounts. The Icelandic government still needs to repay around $4bn to them and all its foreign creditors.

Iceland isn't out of the gutter quite yet, as its private sector and households are still holding a lot of debt. This is preventing the private sector from investments and is preventing households from increasing consumption. It seems as if the entire country is busy deleveraging, but without affecting growth that much. The next step to an even higher growth rate would be to easily remove the capital controls set up during the restructuring to prevent money flowing abroad. This is affecting the attractiveness of foreign investments to Iceland. The recovery based on tourism and fishing will soon come to an end if other sectors don’t follow. And to do that they need fresh money and a stable financial system ready to lend again. From the way they started the recovery it seems they will be able to achieve that.

No, it still isn't applicable to Greece

The whole story made Iceland often recognized as yet another example of the success of currency depreciation (and capital controls) that should be allowed in Greece (once it exits the euro of course). However, Iceland is a much different economy than Greece. First of all, it's an export oriented, small, open economy with a bit over 300,000 people living there. While its exports account close to 60% of GDP, Greek exports are just over 20%. Another crucial difference is that in Iceland, people pay taxes. The rule of law is strong, implying that political stability will be strong as well. The best proof are the trials against the former PM (this is a strong signal to foreign investors, despite the capital controls which should slowly be removed). Furthermore, it doesn't suffer from a constraining labour market, nor does it suffer from regulations and bureaucracy that stifle market opportunities. It isn't without problems, but these are certainly more easily to deal with than in the case of any peripheral eurozone economy and their pre-existing institutional failures.

The story of Iceland is actually a perfect story of what certain economists have been calling for from the start. Let the risk-takers go under without imposing a cost to the society as a whole. This is why Iceland bounced back quite quickly, not because of the depreciation. We can claim that the depreciation eased the transition but it certainly didn’t cause the recovery, unlike many economists tend to think.

It is precisely because of the defaults made that Iceland was able to bounce back. The alternative was the peripheral Eurozone scenario. Now compare Iceland with the PIIGS; Iceland’s misery lasted for 2 and a half years, while Greece’s is already running for 5 years now, likely to go on even further.

Your description of the problems leads me to the same conclusion I have had for some time now. There is no substitute for sound lending policies. Time after time, banks, companies, individuals, and nations get into trouble from too much debt, and a basic devaluation in the common lending practices which we all learn in our first Finance course.

ReplyDeleteWe could replace all of the myriad and byzantine finance laws with four basic things. First, complete disclosure, and higher and hard limits set on reserve requirement, equity to debt ratios, and down payments for real estate.

You make a valid point. However, there is always a question of what would the optimal level of reserve requirements be, or what is the optimal level of the equity to debt ratio?

DeleteFor example, will setting the reserve requirement too high, in addition to stronger regulatory requirements, reduce lending in a time where we expect banks to support the real economy? On the other hand, in the case of zombie banks there is no point of keeping them going, so is it justifiable to have the capital standards to punish them?

But I agree, in the future design of the banking and financial regulatory reform, the 4 things you mention should definitely be taken into account. However, the new regulatory standards must be designed without the regulators creating an incentive what to invest in (as it happened in the US and in Europe as a prelude to the crisis - I called it the regulatory paradox)

But isn't it also true that a lot of Icelanders had loans in foreign currencies which would mean that the depreciation made the people poorer? However, with all the help depreciation did for its fishing industry and tourism, the people didn’t feel the declines in incomes or the loan repayment problems that much. Nor did they have to bear the losses of the banks which meant that no harsh austerity was needed – just a short boost from currency depreciation in order to support their structural reforms.

ReplyDeleteKnowing your stance on currency depreciation, wouldn’t you agree that this was actually beneficial in the end, and that Greece would have benefited from it? They also have a strong tourism sector, and particularly now in the summer. If they did it before the summer it could have benefited them already.

But they didn’t so we’ll never know just how benefitial depreciation would have been, no matter how big the initial impact on Greek personal wealth would be. They’re having a silent bank run anyway and have pulled out most of their cash holdings out of the country.

You are talking about savers who pulled out their cash, which is a true fact, but the real problem would affect debtors, i.e. all those people who have a foreign denominated loan.

DeleteAnd yes, Icelanders had a lot of foreign denominated loans, but in Greece, in the case of a return to Drachma, everyone would have had foreign denominated loan repayments to cope with.

The analogy I’m making here would be more similar to the case of Argentina, rather than Iceland, where domestic wealth was literary expropriated in an attempt to devalue the currency (moving the dollar-peso peg from 1:1 to 1:4), after which the people started with the actual riots and the turmoil began.

Repeating this scenario in Greece will destroy any chance of political stability and could produce a potential dictator or continuing political instability (from which Greece has suffered before and could easily repeat again). This is dangerous as it prevents further consolidation and leads to a self-fulfilling downturn of the country's political and economic system (see more on that here).

Finally, as I pointed out in the article, Greece and Iceland are institutionally very different countries and what presumably worked in one need not be applicable to the other. My point here is on the situation in each country's labour market (I'm referring to the point when Iceland was in deep trouble), efficiency of their public sector, tax revenue collection and the rule of law. With or without depreciation, signals to foreign investors will depend a lot on the efficiency of these factors.

Very interesting. I wonder what would have happened had the United States chosen to let one of its big banks fail? I am not proud of the fact that greedy individuals in our country helped foment such a widespread collapse.

ReplyDeleteCurious - does the UK spell cheap as cheep?

It's hard to predict what would have exactly happened, but some claim it's possible that the slump would have been bigger and the recovery faster. Then again who knows. Perhaps the shock to the system would be too big to recover that quickly.

DeleteAnd "cheep" is a misprint, thanks for pointing it out.

Every week-end I used to pay a fast visit this site, because I’d like enjoyment, because this web site conations certainly fussy material.http://www.vmwexpress.com/services/asset-recovery

ReplyDeleteHello Everybody,

ReplyDeleteMy name is Mrs Sharon Sim. I live in Singapore and i am a happy woman today? and i told my self that any lender that rescue my family from our poor situation, i will refer any person that is looking for loan to him, he gave me happiness to me and my family, i was in need of a loan of S$250,000.00 to start my life all over as i am a single mother with 3 kids I met this honest and GOD fearing man loan lender that help me with a loan of S$250,000.00 SG. Dollar, he is a GOD fearing man, if you are in need of loan and you will pay back the loan please contact him tell him that is Mrs Sharon, that refer you to him. contact Dr Purva Pius,via email:(urgentloan22@gmail.com) Thank you.

This article is actually remarkable one it helps many new users that desire to read always the best stuff. face value of whole life insurance

ReplyDelete