Clash of ideas: Sumner vs Kling

Scott Sumner has produced a post providing a neat introduction to the theory of money and monetary shocks. He did so in 9 short, concise and very interesting lessons (which he attempts to update regularly). I recommend it to anyone interested in some of the basic foundations of the monetarist school of thought (and NGDP level targeting).

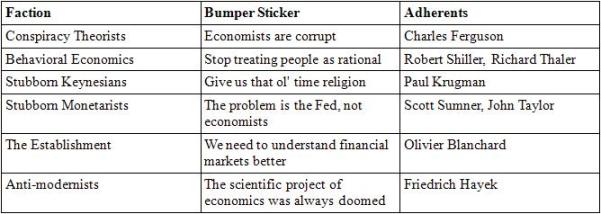

On the other hand, Arnold Kling responds to Sumner's ideas calling upon some of his own previous essays on the state of macro, providing the answer of "what's wrong with the economics profession". These essays are also a welcomed reading for those interested in basic macro theories. Kling summarizes the main factions and explains each of them, starting of with conspiracy theorists and behavioral economists in the first essay, keynesians vs monetarists in the second, and the establishment vs anti-modernists in the third:

I recommend first reading Sumner's posts and then switch to Kling's second and third essay as a sort of a direct response. It could be a nice weekend read.

Here are some of the most interesting ideas. In his first two texts Sumner explains that it's monetary shocks, not real shocks that cause recessions:

"...real shocks don’t matter (very much) for business cycles. The tsunami [in Japan, March 2011] did cause a temporary dip in industrial output, but nothing severe enough to constitute a recession. However when you turn your attention to the labor market you can really see how little real shocks matter. Real shocks do not cause big jumps in unemployment. ... Recessions are caused by unstable NGDP, which is in turn caused by unstable monetary policy ... But it’s not a tautology that the recessions themselves are caused by monetary policy, indeed it’s surprisingly difficult to explain why NGDP instability causes unemployment to fluctuate so much. Especially when the NGDP shocks are caused by rather obvious changes in monetary policy, rather than errors of omission."

While in the final post he explains the causal relationship between tight money and lower output and employment: (a brief summary of the model is also presented here)

"Tight money leads to lower NGDP, which reduces output and employment. ... money is non-neutral in the short run; a change in M leads to a change in output, not just prices... The P/Y split is determined by the slope of the SRAS curve, which reflects the degree of short run wage/price stickiness.

In the long run wages and prices adjust, and hours worked/output return to the natural rate. Of course like any macro model, it simplifies certain aspects of reality. For instance, during a depression investment may be postponed and workers may lose touch with the labor market, and hence there may be a permanent loss of output. However I’d argue that the permanent effects are relatively small, as we saw in the strong bounce back after the Great Depression.

Another non-neutrality can occur if workers have “money illusion,” which means they confuse nominal and real wage changes. For this reason, the bell-shaped distribution of wage rate changes has a discontinuity at zero percent—workers are irrationally reluctant to accept nominal wage cuts [a questionable assumption about the mentioned irrationality]. Thus very low trend rates of NGDP growth, per person, may lead to a higher natural rate of unemployment. ...

Putting aside these special factors, most US business cycles are a pretty simple phenomenon. Because of excessively tight money, NGDP growth slows relative to what was expected when labor contracts were signed. Because hourly nominal wage growth is very slow to adjust, a sharp slowdown in NGDP growth raises the ratio of W/NGDP, which leads to fewer hours worked and less output. It may take many years for the labor market to fully adjust. (Note: if NGDP had started growing again at 5% in mid-2009, we’d be mostly out of the recession by now. The recovery was slowed by further unexpected (negative) NGDP growth shocks after 2009.)"

In addition to these explanations of the monetary business cycle I encourage readers to read Sumner's explanations of fiat money, the quantitative theory of money, and the crucial role of expectations in monetary policy.

I have to say that Sumner provides an excellent explanation of how macro shocks work and how they get translated across the system. However, his starting point is tight money which I believe wasn't the case in the current crisis (even though this is the crucial assumption market monetarists make). In addition, Sumner emphasizes that the current recession is an AD shock, and that it could be solved by monetary stimulus via influencing forward-looking expectations. This is where I disagree and align more closely with Kling's approach:

"...stubborn Keynesians and stubborn monetarists have put their debate right back to where it was in 1970.

Many other economists see the current macroeconomic situation as having unusual characteristics. Some emphasize that financial crises tend to produce long, deep recessions, as Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart have documented in This Time is Different. Others emphasize structural factors, including those I described in “What if Middle-Class Jobs Disappear?” Neither stubborn Keynesians nor stubborn monetarists see a need to take into account financial markets or structural unemployment. Instead, they take the view that any desired macroeconomic outcome can be achieved with the right fiscal and monetary policy approach.

Just as in 1970, the Keynesians emphasize fiscal policy and favor discretionary policies. And just as in 1970, the monetarists emphasize monetary policy and favor rules. Each side is certain that it is correct, although in my opinion both sides are probably wrong."

He goes on further to explain the consensus of mainstream economics and their shortcomings:

"Like the economy, the modernist economic project goes through cycles. When the economy has undergone a long period of low unemployment, macroeconomists become increasingly confident that their models and policy prescriptions are working. Like the rooster believing that his crowing brings the sunrise, they take credit for the good times. ... in the 1960s, it was fashionable to boast about “fine-tuning” the economy. The boom that began in the late 1980s and took off in the 1990s was proclaimed “The Great Moderation,” and ... Alan Greenspan was viewed as “the maestro” by macroeconomists of all political persuasions.

When something goes wrong, the macroeconomic profession enters a period of brooding introspection, with patches applied to the previous models. ... in the 1970s, the fine-tuners were beset by a combination of high inflation and high unemployment that was inexplicable within the models that had worked so well in the 1960s. The 1970s and 1980s were spent arguing and patching ...

Now that we are experiencing another major downturn in the economy, the mainstream modernists will be doing another round of patching. ... Once the economy recovers, I predict that the patching exercise will settle down. At some point, economic strength will have persisted long enough that macroeconomists will believe that they have overcome their previous shortcomings and arrived at models that are robust. A consensus will form, and leading macroeconomists will write once again that “the state of macroeconomics is good.”

And the whole thing will repeat itself when the economy goes into a downturn again. This is where PSST kicks in:

"...Those of us who hold this view [anti-modernism] do not believe that small models can be used to explain and control a complex economy. Instead, we believe that the complexity is irreducible. The economy is too intricate to be understood by any one individual. As Leonard Read famously wrote, nobody knows how to make a pencil. By the same token, nobody knows how to create a job.

I have tried to sketch the ways in which a complex economy can suffer unemployment in a couple of papers on what I call Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade (PSST). The implication of these ideas is that job creation requires local knowledge of entrepreneurs, and this must be acquired through time-consuming trial and error. It is not clear what fiscal or monetary policy can do, if anything, to speed this process.

Finally, his insightful conclusion on the "state of macro":The PSST explanations for unemployment cannot attain the modernist standards of mathematical precision. By those standards, it is another exercise in hand-waving or pulling explanations out of the air. However, I think this may be the best that anyone, modernist or otherwise, can do."

"If I am correct, then the “million mutinies” we are experiencing are the normal cyclical response of the economic profession to adverse events that are beyond our ability to control. The economy presumably will recover, and professional self-confidence will rise along with it. But the modernist project of technocratic tuning of a complex economy is, as Hayek warned, beyond our ability to undertake successfully."

Amazing post, thank you!

ReplyDeleteI havent read Klings essays (too bad weekend passed :D ), hope ill get some time these days to do it.

"Instead, they take the view that any desired macroeconomic outcome can be achieved with the right fiscal and monetary policy approach."

Im not really sure that is at least what monetarists think, on the other side it is also question - what is the desired outcome? I think that is where huge difference lays* (*i hate this verb, never sure if im correct -_-).

"I have tried to sketch the ways in which a complex economy can suffer unemployment in a couple of papers on what I call Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade (PSST). The implication of these ideas is that job creation requires local knowledge of entrepreneurs, and this must be acquired through time-consuming trial and error. It is not clear what fiscal or monetary policy can do, if anything, to speed this process. "

from my perspective the main market-monetarist argument in favor of monetary policy is that it should do what it is supposed to do - manage supply of money according to a rule and correct its mistakes (and there were many), and not try to fix this or that "problem". Its outcomes should be as close as possible to outcomes of a market based system. Then complex economy will manage itself best it can. Fiscal policy goal is not to be neutral, at least i dont think it could be even if they tried.

Greets

Isn't that Kling's point though? That it's hard to determine how will monetary rule-oriented outcomes be as close as possible to the market based outcome? I'm all in favour of rules vs discretion, don't get me wrong, but I feel that Kling has a point in stressing that the economy is too complex to be guided by fiscal or monetary policy rules, at least when times are bad (they seem work well when times are good, I presume).

Delete"but I feel that Kling has a point in stressing that the economy is too complex to be guided by fiscal or monetary policy rules, at least when times are bad (they seem work well when times are good, I presume)."

DeleteBasically I agree, but its not about policy guiding a complex system, from my point it is policy not distorting (or least distorting) a complex system. Economy is complex and market is the best system that manages that complexity - this is something we should always push in any debate. But, we can't close out eyes to the fact that we do have monetary and fiscal policy to worry about, and these are not going anywhere soon. Thats why free market economists must push the debate in direction of making policy less distorting.

Regarding the degree of being close to a market outcome, NGDPLT is closer to a free banking outcomes than inflation targeting (as free bankers say), and very similar to Hayeks MV idea. Outcomes will not always be optimal but I think we have to use what we know is the best at the moment (even though a lot of very smart people still argue in favor of IT) Thats my point - get the monetary policy right (or best you can), and then see where are the other failures. I liked one post by mr.Christensen where he stated that, even though monetary policy may be that last equation in the model, it determines if we live in keynesian or RBC (or some other) world. Illusion of ZLB and previous fail of monetary policy is the reason we live in keynesian world now. Fix that and then behold the "true" size of the structural problem.

I write "from my point" because obviously I dont fully agree with Sumner on all of his points. Also, he often proclaims something but then in comments section he sort of mellows it down.

Btw, have you seen/heard of Calomiris' book/paper on institutional backgrounds of unstable and inefficient banking systems? *book is not out yet but paper is. Ill try to read it these days, I'd love to hear your thoughts since I feel its your area of expertise.

Greets

I absolutely agree that counter-cyclical policies should be less distorting, and I would always prefer to have market-based economists running the show, to interventionist economists. In that sense I think NGDPLT could be a good idea, but not necessarily in kick-starting the recovery - and this brings us back to the previous debate we had :)

DeleteAs for the paper you mention, no I haven't had the chance to read it yet, but I've put on my pile now

Thank God for computers, otherwise my pile would burry me ;)

DeleteInteresting comparsion

ReplyDelete