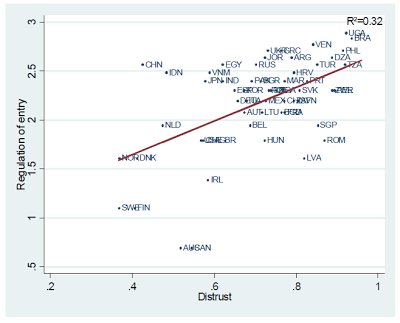

Why do people in societies with low levels of trust advocate higher regulation?

An insightful working paper by Aghion, Algan, Cahuc and Shleifer can give us a possible answer to this question:

|

| Source: Aghion, Algan, Cahuc & Shleifer (2009): "Regulation and Distrust" NBER Working Paper 14648, pg. 9 |

"In a cross-section of countries, government regulation is strongly negatively correlated with social capital. We document this correlation, and present a model explaining it. In the model, distrust creates public demand for regulation, while regulation in turn discourages social capital accumulation, leading to multiple equilibria. A key implication of the model is that individuals in low trust countries want more government intervention even though the government is corrupt. We test this and other implications of the model using country- and individual-level data on social capital and beliefs about government’s role, as well as on changes in beliefs and in trust during the transition from socialism."

The emphasized sentence is particularly important from a policy-making perspective in transitional economies, which are more likely to have lower levels of interpersonal trust, in addition to a low level of trust in corporations, the legal system or political institutions. The essential finding is that in countries with lower levels of social capital, people support more government intervention in the economy. This becomes even more obvious in times of crises. And what is particularly intriguing is that even though the people know the government is corrupt and inefficient they would still prefer things to be (over)regulated rather than to be left "at the mercy" of an uncivic surrounding. Or the generalize, "people in countries with bad governments want more government regulation".

Formal vs informal institutions

This seemingly paradoxical finding is somewhat logical if one thinks about the interrelation of a country's formal and informal institutions. If formal institutions are weak and inefficient, meaning that if the rules in society are poorly defined and offer too much scope for corruption, then informal institutions will adjust accordingly and this will first and foremost affect the accumulation of social capital (people start loosing trust in the system). The relationship works in both ways; if the 'rules of the game' are defined to be inclusive, then the accumulation of (let's call it) democratic capital will eventually lead to a change in customs, norms and trust in a society (i.e. our informal institutions).

The intuition of the paper explains this further:

"In this model, when people expect to live in a civic community, they expect low levels of regulation and corruption, and so invest in social capital. Their beliefs are justified, and investment leads to civicness, low regulation, and high levels of entrepreneurial activity. When in contrast people expect to live in an uncivic community, they expect high levels of regulation and corruption, and do not invest in social capital. Their beliefs again are justified, as lack of investment leads to uncivicness, high regulation, high corruption, and low levels of entrepreneurial activity. The model has two equilibria: a good one with a large share of civic individuals and no regulation, and a bad one, where a large share of uncivic individuals support heavy regulation."Measuring social capital

Which of the two equilibria does your country belong to? Perhaps this will help:

|

| Source: Interpersonal trust index |

Those with a darker red color seem to have less interpersonal trust (the overall level of the trust index is calculated as 100 + (% of those who say that most people can be trusted) - (% of those who say most people cannot be trusted)). See here for more details, individual country data, continental maps and tables. Some of the countries on the bottom of the list are Trinidad & Tobago, Turkey (!), Rwanda, Cambodia, Indonesia, Ghana, Brazil, and from European countries Cyprus and Portugal. On the other hand, the top 10 are the 'usual suspects' Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Switzerland, New Zealand, Australia, Nederlands, Canada (countries that top the indicators of economic and personal freedoms), however with a surprising inclusion of China (4th place), Saudi Arabia (7th) and Vietnam (8th). A possible explanation of the lower end of the spectrum could be (among others) conflicts in the past or large ethno-linguistic fractionalization. On the upper end the three outliers could perhaps be explained by lower inequality or even a long-lasting autocratic rule.

There is an interesting line to draw here between the countries of the former socialist bloc and countries who haven't interrupted their socialist/autocratic rule. Almost all countries that have undergone a transition from socialism (even those with an early EU accession) experienced lower levels of interpersonal trust.

On the other hand the 3 outliers (we can very well add 13th ranked Belarus to the picture) have had a long time without a political crisis. This has perhaps led to lower uncertainty over regime change, and despite the regime being autocratic, the population has been able to adapt to the existing environment and accumulate a higher level of social capital. Countries which have experienced significant political change and/or persistent conflicts have naturally depleted their accumulated social capital.

Transition from socialism and depletion of social capital

On the other hand the 3 outliers (we can very well add 13th ranked Belarus to the picture) have had a long time without a political crisis. This has perhaps led to lower uncertainty over regime change, and despite the regime being autocratic, the population has been able to adapt to the existing environment and accumulate a higher level of social capital. Countries which have experienced significant political change and/or persistent conflicts have naturally depleted their accumulated social capital.

Transition from socialism and depletion of social capital

It would be very interesting if we could compare the relative levels of trust a couple of years before the fall of socialism and a couple of years after. Going back to the Aghion et al paper, their finding is that after the transition social capital in every transitional economy decreased.

In the paper the authors interpret a transition from socialism as a radical reduction of government control in societies with low levels of trust. Their consequential prediction is that this has increased corruption and the demand for government control, while decreasing output and short-run social capital. But what if these countries didn't have a low level of trust before the transition? What if these countries were similar to Vietnam, China, Saudi Arabia or Belarus? That would imply that the transition itself (perhaps because it was done under suspicious conditions) led to a depletion of the existing social capital.

The paper observes four different datasets in which the authors asses trust (from the World Values Surveys): 1981-84, 1990-93, 1995, 1999-03 (so exactly the necessary series to observe the effect of the fall of socialism). They use this dataset for 57 countries (most of the aforementioned included).

The static correlation data imply the following relationships between trust in different types of institutions within a country (particularly interesting is the regulation on the minimum wage - 3rd graph):

In the paper the authors interpret a transition from socialism as a radical reduction of government control in societies with low levels of trust. Their consequential prediction is that this has increased corruption and the demand for government control, while decreasing output and short-run social capital. But what if these countries didn't have a low level of trust before the transition? What if these countries were similar to Vietnam, China, Saudi Arabia or Belarus? That would imply that the transition itself (perhaps because it was done under suspicious conditions) led to a depletion of the existing social capital.

The paper observes four different datasets in which the authors asses trust (from the World Values Surveys): 1981-84, 1990-93, 1995, 1999-03 (so exactly the necessary series to observe the effect of the fall of socialism). They use this dataset for 57 countries (most of the aforementioned included).

The static correlation data imply the following relationships between trust in different types of institutions within a country (particularly interesting is the regulation on the minimum wage - 3rd graph):

|

| Source: Aghion, Algan, Cahuc & Shleifer (2009): "Regulation and Distrust" NBER Working Paper 14648 |

However, more importantly they prove the relationship between low trust and the demand for more regulation (the demand for trust variable is calculated from a couple of World level surveys according to the specific questions asked - see the paper for details).

In their further analysis they imply similar findings; positive relationship between distrust and more government intervention (measured through both price and wage controls for example), but I failed to see a coherent analysis linking the levels of distrust a couple of years before the start of the transition and after the transition. They only look at the level of distrust in transitional economies in the year 1990, and come up with the following graph:

|

| Source: Aghion, Algan, Cahuc & Shleifer (2009): "Regulation and Distrust" NBER Working Paper 14648 |

Along with this table in which they show the initial higher distrust in transitional economies with comparison to OECD countries.

I would argue that this is still a bit late to conclude that former socialist countries had initial lower levels of trust. The transition varied for different countries, but in 1990 it was evident to the people that things were changing and uncertainty was surely high, regardless if the people were looking forward to the change or against it. I would rather compare the level of trust in 1981-84 to get a more precise picture.

Evolution of social capital

The paper actually does look at the evolution of social capital in transitional economies and according to the graph below they conclude that distrust has increased in all transitional economies.

Evolution of social capital

The paper actually does look at the evolution of social capital in transitional economies and according to the graph below they conclude that distrust has increased in all transitional economies.

|

| Source: Aghion, Algan, Cahuc & Shleifer (2009): "Regulation and Distrust" NBER Working Paper 14648, pg. 9 |

Their statistical estimates verify this trend. However, they tend to draw a conclusion from this which I find rather far-fetched: "Liberalization of entrepreneurial activity starting from a low level of social capital has increased corruption, invited a demand for greater state control of economic activity, and reduced trust." How can we be so sure that they started of with a low level of social capital? The authors use the figure depicting the level of trust in 1990, but this, in my opinion, is not enough to draw such an implication.

A noteworthy finding

Overall, the conclusions of the paper are certainly noteworthy in helping us understand and explain some of the interaction between formal and informal institutions and how they help shape economic outcomes. This paper has certainly proven that social capital (regardless of how we think about it, define it or measure it) affects the society's institutional development, and more importantly the people's preferences towards government intervention, despite its (in)efficiency.

I would, however, like to see an extension to the paper trying to explain the aforementioned autocratic outliers. If they undergo a transition to an inclusive democracy, will it be easier for them to do so because of high existing levels of social trust, or will they succumb to the same scenario of transitional economies? The Aghion et al paper indirectly implies that their high levels of social capital will be helpful, but I fear that when regime uncertainty kicks in, social trust immediately declines. This wouldn't mean that social capital isn't important in shaping formal institutions, it simply means that the initial line of causality goes the other way around.

Thnx for the great post about this paper. I particiated a few facebook discussions on this topic and the paper came up. Didnt get time to read it, now I dont have to :D. I like the fact that you mentioned transition economies and the question of what was going on there before early 90s. Idea that people who distrust each other and the government always want government involvement always baffled me. There was an interesting paper on the similar issue few years back, but it involved efficient and inefficient welfare states where they concluded that countries with lower as with higher trust in their fellow citizens had bigger welfare states, but the difference was efficiency (those with more trust being more efficient). Countries in the middle had smaller welfare spending.

ReplyDeleteGreets!

Sounds interesting, do you remember which paper that was?

DeleteIm pretty sure its this one, it was assignment while studying and i forgot to pull it down from the university server before passed the exam. http://econ.sciences-po.fr/sites/default/files/file/yann%20algan/IZA.pdf

DeleteThanks for this, I'll make sure I give it a glance

DeleteIf you want to study the process of the dissolution of social capital then watch my nation the USA. Once there was a high level of trust of both formal and informal institutions and among people. But a rapacious ruling class has eroded that. Now, every new or proposed law has be be propagandized by the government because the citizens simply do not trust them at all. We trust neither their stated reasons, nor the expected results of any new measure.

ReplyDeleteWhen would you say this process has started?

DeleteTrust and distrust seem to go hand in hand with more or less regulations.

ReplyDeleteexcellent article!

ReplyDeleteSimply by observing the info from the map you linked to, is it possible that social capital and interpersonal trust is higher in societies who have a bigger size of government? The stronger the role of the state, the people feel more safe, perhaps?

ReplyDeleteNo, not really, there are many examples that point to otherwise. I don't think there is any strong correlation between the size (role) of government and interpersonal trust. Things mentioned in the text, like low uncertainty, lack of ethnic or other conflicts etc. seem to have a much stronger predictive power.

DeleteSocial capital implies institutional strenght. If people trust each other more, they are also more likely to trust their government and "the system".. Hence the protests.

ReplyDeletePerhaps this trust can be used to explain the recent protests in Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia, etc? After all these are the countries with the lowest levels of interpersonal trust in the world..