The reverse savings glut

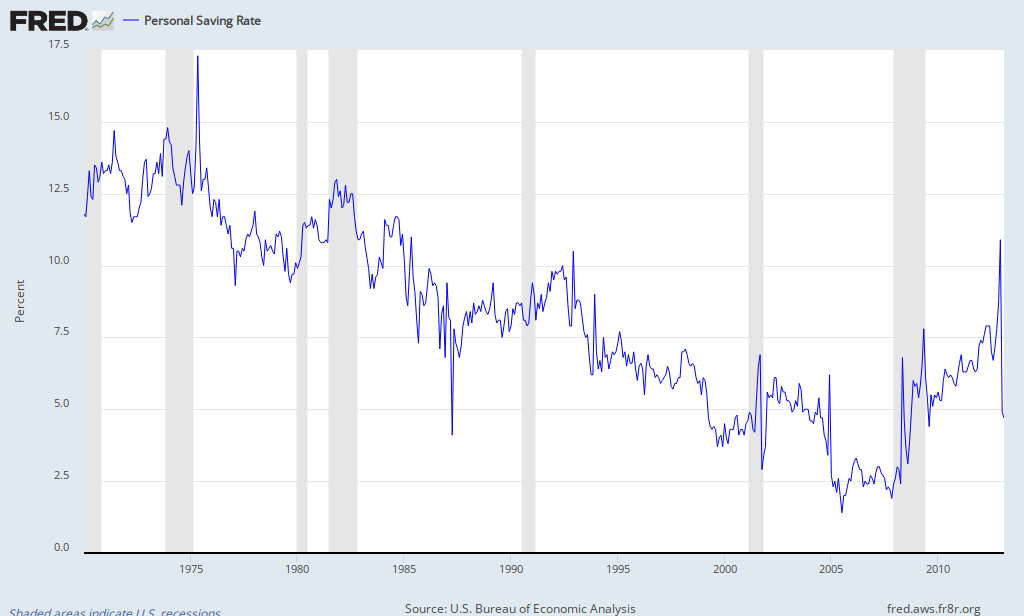

The personal savings rate in the US has experienced a steady decline in the past 30 years, up until the recent crisis:

From the Economist:

|

| Source: FRED |

"The drop began in the 1980s, perhaps because the Great Moderation made people less fearful of economic uncertainty. When uncertainty returned during the financial crisis, and as credit conditions tightened, the saving rate shot up. Wage stagnation may also play a role; people expected better living standards and cut back on saving to raise consumption. The saving rate fell again this past January. That may reflect greater economic optimism or the return of the full payroll tax, which lowered take-home pay. Rather than decrease consumption people may have saved less."

A declining savings rate is a worrying signal to the economy as it increases its vulnerability to crises. The reasoning is clear; the higher the leverage of the private sector in pre-crisis times, the stronger the deleveraging will be after the shock. Private sector savings will go up and borrowing will be scarce, implying a lot of underutilized resources.

The reversal of the trend (following the housing bubble)

So with household debt increasing during the Great Moderation (due to a variety of reasons), the current deleveraging process can hardly come as a surprise.

Why savings went down?

There are several plausible explanations for the decline of the savings rate and an increase of borrowing, particularly in the pre-crisis decade (see graph below - red line). Some claims have been made that households, rather than keeping money in liquid assets, were increasing savings in the form of retirement accounts. The Wall Street Journal had a good report on how automatic enrollment in 401(k) accounts has boosted the number of savers but has decreased the average savings rate. The popularity of such pension accounts could also be accounted to an ageing US population. Another interesting factor in this story is that recently, there has been an increase in the number of savers drawing on their pension plans too early (and hence accepting a penalty for early withdrawal). This only further stresses the gravity of the current financial situation among US households.

The reasons behind the relative decline of savings in liquid assets can be either slow growth of average income in the past 30 years, or a low return on low-risk savings discouraging people to save. The New Yorker did an interesting story on the myth that easy money is hurting savers, recognizing the real problem in which there are a lot of people out of jobs and out of money, so basically cannot save anything at all. Taking all these factors combined (slow personal income growth, low returns on equity, a switch to non-liquid retirement accounts), they could offer a potentially reasonable explanation of why people borrowed more in the past 30 years and saved less, thus exposing themselves to more financial risk. This story is similar to Rajan's Faulty Lines argument.

The reversal of the trend (following the housing bubble)

So with household debt increasing during the Great Moderation (due to a variety of reasons), the current deleveraging process can hardly come as a surprise.

|

| Source: FRED |

However, total household debt as percent of disposable income (green line) didn't experience significant increases until the last decade, and is now on the same level as it has been in the beginning of the 1980s. The housing bubble and the consequential crisis acted as an immediate reverse signal to households who started to save and deleverage, and this process is still far from finished. The balance sheet recession argument seems to be in order; after a significant shock personal savings go up, borrowing goes down, and there is a consequential lack of liquidity in the system. As for the argument for more liquidity to be necessary provided by the government, in the graph below we can see that this has indeed happened during the current shock. The government has provided excess liquidity and increased spending, but this has failed to prevent the deleveraging process, while the savings rate remained high.

|

| Source: FRED |

One could argue that the deleveraging process would have been even stronger without government involvement, but the effect on savings would have still been more or less the same. This is probably due to the phenomenon of a reversed relationship between public and private savings.

So how do we reignite borrowing and reverse the deleveraging process of households and businesses in order to start growing? Who is to say that this is the right approach anyway? A lot of risk has been accumulated (it was perceived to be non-existent) in the pre-crisis decade and as a consequence the system has to undergo significant deleveraging (on the corporate side). The problem of inequality and low income growth on the household side is hardly a short-run issue that can be solved by temporary liquidity.

The proper incentive to break this process is not to cramp the system with public sector spending, but rather to offer different incentives to households and businesses to restore their confidence. The psychological effect of governments restoring confidence doesn't seem to work if these governments are constantly being threatened by unsustainable public finances and outdated welfare models. This is why the confidence to the private sector needs to be restored via cost-oriented incentives. There is no better incentive for a business than a cost-cutting one. It frees up funds and creates the scope for higher production and eventually higher employment.

The proper incentive to break this process is not to cramp the system with public sector spending, but rather to offer different incentives to households and businesses to restore their confidence. The psychological effect of governments restoring confidence doesn't seem to work if these governments are constantly being threatened by unsustainable public finances and outdated welfare models. This is why the confidence to the private sector needs to be restored via cost-oriented incentives. There is no better incentive for a business than a cost-cutting one. It frees up funds and creates the scope for higher production and eventually higher employment.

But according to some economists expectations and uncertainty have either a negligible effect, or one which cannot be measured. I wonder how they interpret this data?

ReplyDeleteGood point. This is after all one of the best indicators of high uncertainty of the private sector

DeleteThe economy appears to be moving foreward but very slowly. Energy production or developmant appears to be expanding at a far great rate in the united states than what we have seen in decades. also housing appears to be coming back. I would be concerned more about the economy next year not now.

ReplyDelete