Monetary and fiscal bubbles after COVID

In the previous blog I analyzed the stunning divergence between the markets and the real economy. I emphasized three particular reasons for why this is happening: (1) huge monetary and fiscal stimuli that started the V-shaped rebound on the markets in March; (2) exuberant (and by all means irrational) expectations driven primarily by the so-called retail investors (the subject of one of my next blogs), and (3) the asymmetry between firms driving the market (the top 5 big tech firms) vs the unlisted SMEs laying people off and declaring bankruptcies.

In this blog I will touch upon the potential instabilities of the first effect: the monetary and fiscal stimuli.

While the stimuli were designed to calm the market panic back in March, its continuation - particularly from the Fed - is creating massive instabilities elsewhere. Specifically, there is ample evidence of a growing monetary bubble, unavoidable fiscal instabilities due to rising debts and deficits, and even a potential corporate debt bubble which, due to the increasing risk of bankruptcy of many businesses, could be a potential blow for the banking industry.

Let us examine the first two in greater detail (the debt bubble will be a subject of a new blog post).

1) Monetary bubble

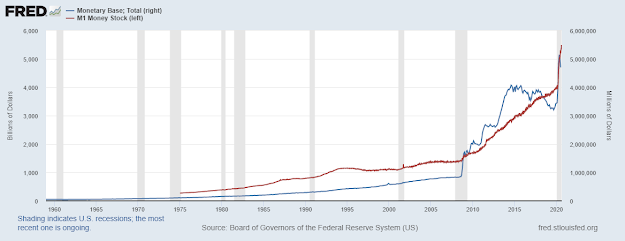

The monetary bubble started as a response tothe Great Recession. The rapid expansion of both the monetary base (M0) and

money stock (M1) has been (wait for it...) unprecedented (see Figure below), but it was deemed

necessary by many economists in order to bring back confidence into the economy

particularly during episodes of rising uncertainty during the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

The 10 years of “QE infinity” fueled the

longest bull market in history. The Fed started to raise rates in 2015 which

decreased the monetary base, but M1 money stock kept rising, meaning that the

markets kept being overflooded with money. The reason this never caused an

inflationary spiral is due to there being almost unlimited demand for the

dollar worldwide. In fact, there is a greater threat of deflation than inflation at the moment for the US economy.

|

| Figure 4. Comparison of M1 money stock and monetary base (M0) in the United States. Source: St. Louis FRED database. |

However, the negative effect that was created in the past decade that is being

amplified today are distorted expectations. Investors expect the Fed to

provide constant liquidity. By keeping interest rates too low throughout

the longest bull market in history the Fed created impetus for another big

bubble, far greater than the one it was criticized for back in 2001 that

resulted in the mortgage crisis.

The market is clearly addicted to Fed stimuli. In order for it to

continue to grow the Fed would need to do more of the same for the next decade,

just as it did since 2009, but this time on levels so high that they will

inevitably cause huge distortions of market signals and potentially send the US

economy into a deflationary Japan-like two decade stagnation.

As a direct response to the pandemic-induced

lockdowns the Fed simply did more of the same: massive quantitative easing in

order to help the economy overcome the panic (M0 and M1 went up by a whopping

30% from March to May 2020). While their reactions coupled with government

stimuli offered the necessary confidence and relief to the wider economy, its

main effect was to send markets back up, thus adding even more distortions

to market allocation decisions and pushing investors back into equities

when the fundamentals are still weak and the markets highly overvalued. It was

like treating a crystal meth patient with more crystal meth.

The Fed, in the medium term, is in a lose-lose

situation. Whatever it does it will risk undermining its credibility and

adding to the instability. If it raises interest rates it will take

liquidity off the markets and almost certainly send the stock market down a negative

spiral. If it continues to push more money into the markets it is entering

deeply into uncharted territory risking a huge collapse in the years to come.

In conclusion, continuous stimulus from

the Fed in terms of lower rates at this point is likely to cause more harm than

good, already in the medium run.

2) Fiscal bubble

Federal debt to GDP in the US has been rising

since the end of 2008. It has risen from 60% before the Great Recession to

around 100% in 2012 and has roughly remained there during the entire

historically long bull market. This was not a fiscally stable position to begin

with, and the COVID pandemic only made it worse, skyrocketing debt-to-GDP to

131% in June 2020 (see Figure 5). This is a larger debt-to-GDP ratio than

during the aftermath of World War II, when the ratio stood at

120% (but has decreased quickly due to a rapid post-war recovery which is an

unlikely scenario today). In 2012 the US was on the verge of “falling from a fiscal cliff” with the political standoff between the President and Congress

triggering significant uncertainty in the economy. The fiscal cliff scenario

was averted but the debt levels remained unsustainably high, and are now higher

than ever before in modern US history.

|

| Figure 5. US debt to GDP ratio. Source: St.Louis FRED data on Total Federal Debt and the real-time US debt clock. |

The federal budget deficit is even worse. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) made a projection of 3.7tn for 2020 which is a staggering

18% of GDP and represents a fivefold increase from the 2019 budget deficit.

A deficit this large will imminently cause major disruptions in the years to

come and will spark fierce debates among economists and call for radical policy

actions. Expect the return of the stimulus vs austerity debate throughout 2021

and 2022 (and possibly beyond). And expect even more political

radicalization as a consequence of austerity and budget cuts to put the

fiscal situation under control. We could even witness another credit ratings

downgrade of the US economy and almost certainly of many European economies.

Forward-looking expectations on the markets

right now are simply ignoring these fiscal realities which will cause

problems in the years to come. And this is before even taking into account the situation with the corporate debt market and inevitable bankruptcies, a topic of the next blog post. Stay tuned.

Comments

Post a Comment